Rediscovering Ginninderra:

Ginninderra Blacksmith's Workshop

The Ginninderra smithy is one of just a few standalone blacksmith shops left in Australia and, as such, was one of the first sites to be listed on the ACT Interim Heritage Places Register; gazetted in 1993. Today, it remains in stable, but poor condition, although, there seems to be no firm plan concerning its long-term management. The workshop has an earthen floor and is constructed of timber posts, slabs and corrugated iron. It contains the remnants of a forge with a small cast-iron door and a petrol engine next to leather bellows.

Blacksmithing was an essential industry and was carried out by part-time smiths at Palmerville in the early days. The first person recorded with any formal training as a blacksmith, never actually worked as one. This was Edmund Ward (1826-1903), William Davis' gardener.

The first professional blacksmith of Ginninderra was James Hatch. In 1860, he built the blacksmith's workshop that still stands on the Barton Highway, today. 1860 was also the year that Hatch married fifteen-year-old Mary Ann Daley at Tumut. Hatch's elder brother, William, moved nearby in 1862, taking up a selection called 'Rosewood'. But James and Mary Ann soon left.

Young Irishman of Jeir, Flourence McAuliffe, became the second Ginninderra blacksmith. Five years earlier, he had married Mary Ann Flanagan, with whom he was to have eleven children. But McAuliffe's tenure was dogged by bad luck. Mary Ann struggled with mental illness and, in 1867, fire took their home and possessions, but not the smithy. Locals helped them rebuild and they were quickly in action again. McAuliffe repaid their generosity by donating land for a school.

Despite McAuliffe being a first-rate smith - with his ploughs winning district prizes - he went bankrupt and left the district in 1876.

Fortune shone more kindly upon the third Ginninderra smith, George Curran. His wife (Mary Ann Hatch) was the niece of the original smith. In the 1880s, the shop was full of activity with two apprentices employed. One of them was his nephew, Harry Curran. The Queanbeyan Age said, 'You can hear the notes, loud and clear, with all their variations, from the anvil of ... Curran's blacksmith's forge'. Chasing a better opportunity, Curran relocated to Bungendore in 1889.

Next, it was the turn of short-term smith, Alexander Warwick. His father was the Canberra blacksmith. Young Warwick was active in organising the One Tree Hill races. Helping him at the anvil, seems to have been Augustus Helmund, the son of a German sign writer from Queanbeyan. After two years, Warwick also left. Like McAuliffe, he too was declared bankrupt.

The last Ginninderra smith remained at the forge for 58 years. This was Harry Curran, who had served his apprenticeship with his uncle, George, at Ginninderra from 1882 to 1889. Harry retired in 1949, aged 82. In 1954, when the Queen visited Canberra, Curran was one of seven elderly 'pioneers' chosen to meet the Royal party. When introduced to the Duke, who said to him, 'You must have worked very hard', Harry's laconic reply to young Phillip was, 'Too right I did!'

The Ginninderra smithy was even used as a polling booth in the 1907 election, the last in which ACT residents were permitted to vote until they were re-enfranchised with federal representation in 1949. For the election of that year, 82-year-old Harry was interviewed by The Canberra Times. The reporter was seeking the views of the district's pioneers, who now had their first chance to vote in 42 years. Harry seemed unconcerned, merely observing that 'things have certainly changed since I last had a vote'.

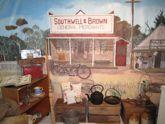

Related Photos

Click on the caption (⧉) to view photo details and attribution.

References

- Bordiss, L., 'The Ginninderra Blacksmith's Workshop: a Heritage Study of the Tools Used by H. R. Curran', Paper of the Cultural Heritage Management Unit of the University of Canberra, Canberra, 2003.

- Bremers, A., 'An Interpretative History of the Ginninderra Blacksmith Shop: from Inception to the Present Day (c. 1859-2011)', Paper of the Cultural Heritage Management Unit of the University of Canberra, Canberra, 2011

- Cosgrove, C. and P. Dowling, Ginninderra Blacksmith's Shop. Conservation and Management Plan, Report to the ACT Heritage Unit, National Trust of Australia (ACT), Canberra, 2002.

- Gillespie, L. L., Ginninderra: Forerunner to Canberra, Campbell, 1992

- Maher, B., In Praise of Pioneers: an Account of the Keeffe and Curran Families - Queanbeyan District, Canberra, 1981

- Newman, C., Gold Creek: Reflections of Canberra's Rural Heritage, Ngunnawal, 2004

- Shumack, S., An Autobiography, or, Tales and Legends of Canberra Pioneers (ed. J. E. and S. Shumack), Canberra, 1967

- Smith, L. R., Memories of Hall, Canberra, 1975

- Warman, M., The Hatch Family in Australia, Canberra, 1981

- Wigmore, L., The Long View: a History of Canberra, Australia's National Capital, Melbourne, 1963

Further information about the Ginninderra Blacksmiths may be found at Canberra Tracks